Our October blog post comes from Team Hamilton's Christine Wallis, who has been thinking about how the circumstances of letter-writing, and letter-writers, leave traces in the archive:

One of the things I’ve been enjoying most about working with the material on the Hamilton project has been the opportunity to get a close look at the letters themselves. What has really struck me is how much can be gleaned from the physical letter; seeing the pen-marks that make up each writer’s handwriting puts us in touch with the individual who wrote it, and helps bring the contents to life – from the carefully neat, via the heavily corrected, to the hurried and barely legible. Our letter-writers come from many walks of life, from servants to royalty, and as you might expect, show real diversity in their writing. For me, this week’s highlight has been this letter from Mary Jackson, Mary Hamilton’s god-daughter, whose handwriting is not easy to read at the best of times. Perhaps she can be forgiven her dreadful writing on this occasion, as it turns out that she is looking after a sick friend:

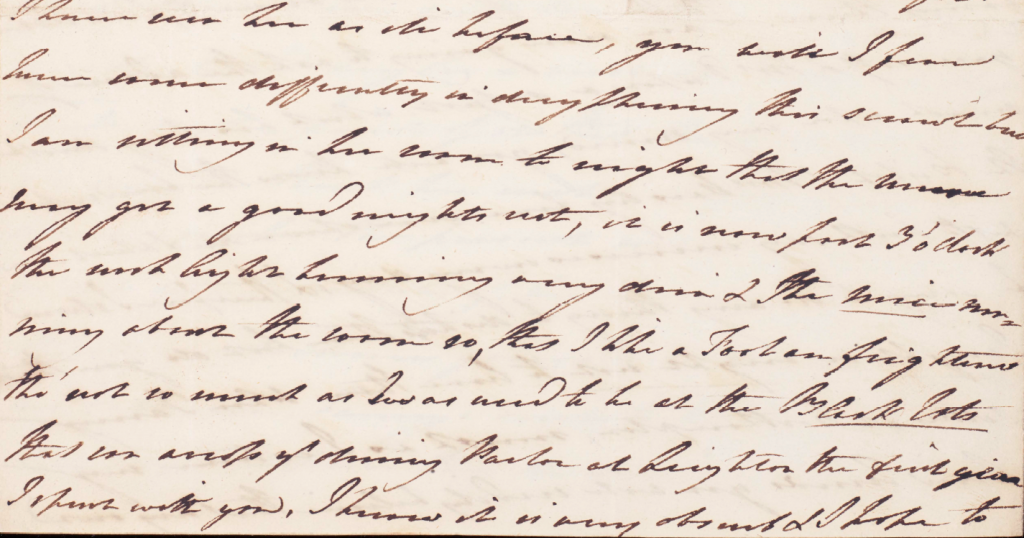

Excerpt from HAM/1/10/2/15

‘… you will I fear have some difficulty in decyphering this scrawl but I am writing in her room to night that the nurse may get a good nights rest, it is now past 3 o'clock the rush light burning very dim & the mice run= ning about the room so, that I like a Fool am frightened tho' not so much as I was used to be at the Black Rats that ran acroʃs ye dining Parlor at Leighton the first year I spent with you…’

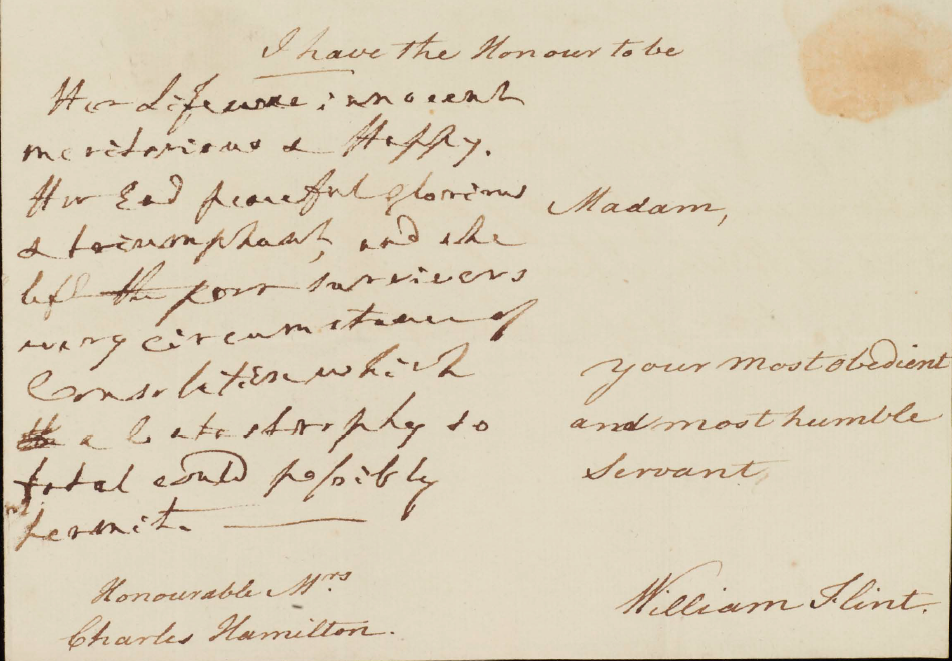

I particularly like the image Mary Jackson conjures up, of sitting and writing in suboptimal conditions, distracted by scurrying mice. While we on the Hamilton team (frequently!) complain about the difficulty of ‘decyphering’ the output of some of our writers, it is in reading letters such as Mary’s that the lived reality behind the document emerges, going some way to account for the condition and form of the documents we work with. Sometimes correspondents will excuse their untidy writing, revealing that they are in a rush, suffering from illness, or, in the case of Mary Hamilton’s uncle Lord Cathcart, recently bereaved. This letter breaking the news of Lady Cathcart’s death in St Petersburg is unusual in being written by a secretary – all other letters from Lord and Lady Cathcart are autographs, mostly on everyday topics such as family news and gossip. In this letter, however, William Flint explains that the rest of the family, though in good health, are ‘in the utmost affliction’ and that Lord Cathcart is ‘unable to write himself’. Nevertheless, Cathcart does provide a short note in an uncharacteristically shaky hand at the end of the letter, and the contrast between Flint’s professional and business-like hand and Lord Cathcart’s distracted scrawl is striking:

Excerpt from HAM/1/4/7/29

‘Her Life was innocent meritorious & Happy. Her End peaceful glorious & triumphant, and she left the poor survivers every circumstance of Consolation which the a Catastrophy so total could possibly permit.’

It is not just the quality of the writers’ handwriting that shows variation – many of the letters include non-standard spellings too. In my previous research I analysed features such as spelling variation to build up linguistic profiles of writers that can tell us about their education, or how they went about writing or copying a particular text, and one pair of writers whose spellings caught my eye are Eleanor and Mary Glover. We don’t know much about Eleanor and Mary. Eleanor was the second wife of the poet Richard Glover, and she and her step-daughter Mary seem to have had a very close relationship; Mary frequently mentions Eleanor’s love and kindness after her father’s death:

‘My dearest mother behaves in the kindest manner to me, she will not suffer me to pay any thing for my board, but I live with her exactly as I used to do when my father was living […] we grow more attach'd to each other every day’ (HAM/1/13/32)

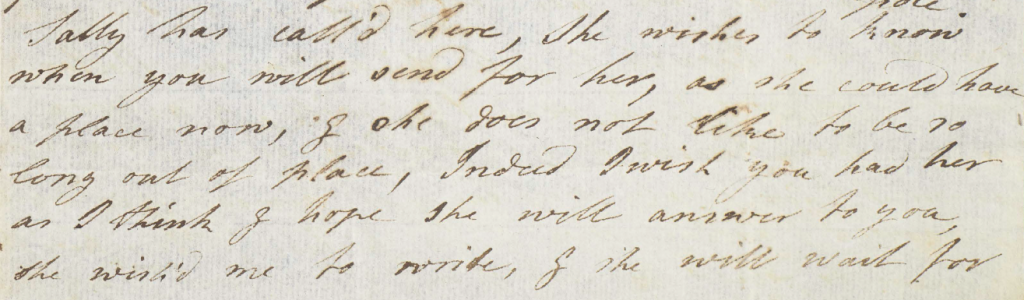

Eleanor frequently says how little she likes writing, and as the years go by it is notable that Mary becomes the more frequent correspondent. Eleanor’s letters include a wide range of non-standard spellings: some are variants which were in common use among eighteenth-century writers, such as cloathing and beleive, while others are more idiosyncratic, such as persuaid and whent. This last spelling is an interesting one, as h-insertion appears elsewhere in Eleanor’s writing (had (‘add’) and his (‘is’)), and is a feature which went on to be heavily stigmatised in the nineteenth century. Mary also uses non-standard spellings, such as least (‘lest’) and misstress. What I found most intriguing, however, is that Mary and Eleanor share a number of spellings, for example, chearful, dutchess, hooping (cough), neice, and peice, which leads me to wonder, did Eleanor teach Mary to write? There is no straightforward answer to this – Eleanor and Mary disagree on spellings like presant/ present, openion/ oppinion and benifit/ benefit – but in this and other features their writing certainly shares some interesting linguistic traits. My final example of variation is in the choice of whether to write, or not. Like Lord Cathcart, many in Mary Hamilton’s network use an amanuensis in times of infirmity or emotional distress, or to pass on good wishes via another writer when the opportunity arose. Sally Barrow, a servant of the Glover family went to work for Mary Hamilton in 1786, and in a fascinating set of exchanges she can be seen negotiating this change in employment. However, she never writes herself, instead sending messages via her employer, Mary Glover:

Excerpts from HAM/1/13/33

Sally has call'd here, she wishes to know when you will send for her, as she could have a place now, & she does not like to be so long out of place, Indeed I wish you had her as I think & hope she will answer to you, she wish'd me to write, & she will wait for Your answer.

This excerpt raises some interesting questions: does Sally send a message via Mary Glover because she can’t write herself? Or perhaps she chose this method as the situation is a rather delicate one; she does not want to turn down the alternative offer of employment unless she can be sure that Hamilton’s job offer still stands. Or perhaps she is using Glover’s higher status and close friendship with Hamilton as a way of applying gentle pressure to speed up her move into the new job. The fact that we are told ‘she wish'd [Glover] to write, & she will wait for [Hamilton’s] answer’ shows that although she is anxious to settle the matter of her future employment and willing to use the leverage of the alternative job offer, she is also reluctant, given her lower status, to appear too pushy in her request. The letters we are transcribing are always throwing up unexpected points – each writer has their own linguistic quirks and stories to tell which hint at the lives behind the letters. The experiences they relate about the details of everyday life, their thoughts and emotions, furnish us with a fascinating window onto eighteenth-century life.

Christine Wallis

October 2020