To mark the release of the Unlocking the Mary Hamilton Papers’ fully-edited correspondence of Mary Hamilton and George IV, Sophie Coulombeau explores the dynamics of their correspondence in this special long read blog:

This is not a love story: Mary Hamilton and George IV

by Sophie Coulombeau, University of York

Introduction

This week, we’re releasing a series of newly transcribed, arranged and edited 240-year-old letters between Mary Hamilton and the future George IV.[1] Largely written over the second half of 1779, these 139 letters between the 16/17-year-old Prince of Wales and 23-year-old Hamilton (who was employed at the time as a sub-governess to his sisters) have in the past been largely treated as “love letters” that show a softer side to the young man who would later become the depraved Prince Regent and unpopular monarch. Biographers of George IV tend to view the affair affectionately or with amusement, referring to the Prince’s “heartfelt… love” and “devotion”.[2] And recent media coverage of the Prince’s side of the correspondence, no doubt drawing on these descriptions, has described the 17-year-old Prince as “lovelorn” and Hamilton as his “secret crush”.

But this approach only tells half the story. Whatever the Prince’s pursuit meant to him, from Hamilton’s perspective it looks remarkably like unwanted sexual harassment. The Prince’s attentions seem to have caused her distress, affected her feelings about her post at Court, and left her with very ambivalent feelings about her future monarch. Her letters and diaries reveal the resourceful strategies she adopted to keep him at arm’s length and preserve her precious reputation intact. They can tell us a lot about gendered court politics of the late eighteenth century, and the ways that women in such an environment might have coped with unwanted attentions from male superiors.

The only published full-length work to date in which Hamilton’s own voice has been given significant space is the 1925 biography Mary Hamilton, afterwards Mrs. John Dickenson, at Court and at Home, from Letters and Diaries 1756 to 1816, which contains selections from her letters and journals edited by Hamilton’s great-granddaughters Elizabeth and Florence Anson.[3] The Anson sisters produced an invaluable and admirable resource, but they adhered to conventions of early twentieth-century life writing – including certain instances of censorship and amendment – that mean a fresh interpretation of the original correspondence is long overdue. Read on for our reconstruction of the letters – and for an afterword drawing on parts of Hamilton’s archive that have never before been published.[4]

Arrival at court

Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III and mother of the Prince of Wales, invited Mary Hamilton to court to act as sub-governess to her elder daughters in June 1777. Hamilton was “astonished” to receive the invitation – “I never in my life had the least desire to belong to a Court”, she wrote to a friend – but it wasn’t the sort of invitation she felt she could refuse.[5]

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

studio of Allan Ramsay

oil on canvas, 1761-1762

NPG 224

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Once in post, Hamilton’s duties were dictated by royal routine and etiquette. Each day, she dined with, walked with and tutored the princesses, and every other evening she was summoned to read aloud to the Queen.[6] It must have been a difficult environment in which to cultivate friendships, since the surviving evidence suggests that life as a courtier was a strange blend of formality and intimacy. Her charges often sent her affectionate notes beginning “My dear Hammy”[7] and she wrote gratefully of the Queen’s initial “kindness”[8] and the King’s “goodness”[9] towards her. But, like other members of staff, she was constrained by an elaborate set of behavioural codes – for example, attendants were not permitted to sit down in the presence of the monarchs and their family – or even to accidentally turn their back upon them. No courtier was ever permitted to forget that they were in the presence of a superior.[10]

Declaration and rejection

In the summer of 1779, when she’d been at court for two years, Hamilton was vulnerable and depressed. As well as struggling beneath the weight of her Court duties, she’d recently been bereaved of her mother (her father had died some years previously) and no fewer than five close friends aged under forty years old. In the midst of this, the Prince of Wales seems to have declared his love for her and begun an ardent pursuit of her affections.[11] On 25th May 1779, he writes, “Your manners, your sentiments, the tender feelings of your heart, so totally coincide with my ideas, not to mention the many advantages you have in point of person over many other Ladies, that I not only highly, esteem you, but even love you more than Words or ideas can express”.[12]

Five days seem to have passed before Hamilton replied to the Prince’s bombshell. On 30th May she responds to this declaration with a firm negative: “I can without injuring my honour accept Your friendship – to listen to more I should justly forfeit the esteem you say you have for me”.[13] She also flatly forbids him to send her gifts: “[D]o not offend my delicacy again by sending me presents – I acknowledge I have a little pride of heart therefore lay me under no further obligations of that kind – the one you gave me some time ago was a pleasing mark of friendship therefore I scrupled not to accept it – the rest were superfluous & I shall return them”.[14]

The Prince seems, at first, to accept the rejection. On 1 June, he responds promptly: “[A]s you say you can not consistently with your honour listen to such proposals, I take heaven itself to Witness that I will not intentionally do anything which I think will displease you, and therefore I will as seldom as possible touch upon a subject which is painful to you…”[15]

King George IV

by Richard Cosway

watercolour on ivory, circa 1780-1782

NPG 5890

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Continued pursuit

But the Prince’s resolution doesn’t last long. On June 6th, he begs Hamilton to meet him alone in the Butterfly House at seven o’clock, “as I have but a single question to ask of you”.[16] Apparently this attempted rendezvous didn’t go to plan, as the next letter from the Prince acknowledges “how much struck and astonished you was with my sudden appearance… at so unusual a place, & at so unusual an hour”.[17] He later, feebly, claims that the important question he had for Hamilton was whether or not she was in good health. And, contrary to his promise to moderate his language, he adds, “I shall love and esteem you as more than any friend, during the whole of my life”.[18]

Hamilton’s response to this letter doesn’t survive, but she apparently used it to take the Prince to task in some way. In his next letter, dated 20th June, he reproaches her for her “too cruel words”.[19] Apparently these included a firm request to stop writing to her, since the Prince responds, “I consent according to your desire to drop our clandestine intercourse by Letter, unless something particular happens concerning which I wish to ask your advice”.[20] It’s unclear whether the caveat belongs to her, or to him.

As June turns into July, the Prince continues to give vent to his feelings. On 24th July he tells Hamilton, “[I] doat upon and adore [you] beyond the idea of every thing that is human”,[21] and on 26th July he swears, “I would now, ay most willingly, were this the condition of my being eternally united to you, retire to some unknown place, give up all my future prospects in this World, and all its pageantry, and live in retirement, happiness, and love with you”.[22] He persists in sending her gifts – a toothpick case,[23] a smelling bottle[24] and a bracelet[25] – despite her firm request to the contrary. He also pesters her for a lock of her hair: “I shall keep it in your absence as the representative of my dear friend & love it accordingly”.[26] George’s letters later this month indicate that he believed Hamilton was going to send him her hair in return, but there is no evidence that she ever did so.[27]

Is this what the Prince was after? Lock of hair preserved in a pocket book belonging to John Dickenson, whom Mary married in 1785 (Lancashire Archives, DDX/274/6. We are grateful to the Lancashire Archives for their permission to digitize this holding and reproduce this image).

Developing strategies

Hamilton never swerves from her consistent and emphatic rejections of George’s advances. But it’s clear that she’s painfully conscious of the power imbalance between them – and that she feels she has to walk a fine line to avoid on the one hand displeasing the Prince, and on the other creating suspicion in the King and Queen that she’s encouraging their son’s advances.

She employs a range of strategies to keep her balance on this line, which show her adapting shrewdly and creatively to the Prince’s attentions. By July, for example, she seems to have realized that telling him not to write to her is pointless. Instead, she keeps careful records of the correspondence, filing the Prince’s letters by date and instructing him to return or burn her own letters rather than keep them.

She is also careful to repeatedly state, in writing, her objections to his pursuit, and her fears about how his partiality for her might affect her reputation. For example: “I am tortur’d with some uneasy reflections which I cannot stifle… remember Sir my fame is dearer to me than life. for however innocent the motives which influence, the world would naturally, & particularly two persons would put a cruel construction upon a secret & clandestine correspondence were it ever to transpire”.[28] She is careful, too, to explicitly remind him of his station in life, so different from her own. “You forget surely that Providence has placed you in a situation which it is, & will be your duty to support in every respect, & act up to in every instance”.[29] She also praises his parents (her employers) with great fervour.[30]

Perhaps recognising that the Prince was never going to stop sending her presents no matter how much she pleaded, Hamilton begins to return them. On 3rd July: “I do not choose to accept the present, be so good then as to give me a proof of your friendship – take it back without being offended – once more I tell you I will not – I never will lay my self under obligations I have not the power of returning”.[31] And, shortly thereafter, “I will not accept any more presents – I will not lay under any, any obligations. Mine is not a friendship upon sordid vulgar terms”.[32] Her firmness on this point reminds us that, at this time and in this place, gift culture bore a raft of meanings that might not be immediately clear today. In her recent book The Game of Love, Sally Holloway explains that “[m]aterial objects from letters to locks of hair held a central place in rituals of courtship, and were used to negotiate, cement and publish a match… the exchange of gifts was a crucial form of language”.[33] Hamilton keeps repeating the word obligation with regard to the Prince’s unwanted gifts. Clearly, she is alert to the symbolic power of gifted objects and she wishes to make herself crystal clear that she is not, and does not wish to be, in the Prince’s debt.

Emotional blackmail

By 23rd July, Hamilton seems to have mentioned to the Prince (in a letter that has now been lost, or else in person) that she wanted to leave her position at Court.[34] In one letter, she tells him that she loves “independence & Liberty” and hints that this desired state is incompatible with her current employment.[35] This is a really striking moment. In one respect, Hamilton undoubtedly means that she wishes to be free of her duties, and to manage her own time. But it’s far from clear that this is her only meaning. “Independence” and “liberty” are very charged words in the year 1779. In fact, they’re exactly the words that the American colonists are using to argue for secession from a tyrannical monarch – the Prince of Wales’s father, George III. It’s possible, I think, that Hamilton is deploying that vocabulary to communicate to the Prince the cruelty of the position in which his attentions are placing her.

In response, the Prince threatens to kill himself if she leaves. “I am thoroughly resolved not to survive your loss. Think not that this is the resolution of a giddy, rash, wild young man it has arisen from the constant contemplation of a strong & sound mind”.[36] Hamilton’s response to this threat is refreshingly phlegmatic: she replies, shortly, “I repeat I will not go at present”.[37] George makes his threat again a couple of days later: “you never will think of making use of that liberty… unless you wish to see me lie breathless and lifeless at your feet”.[38] Once again, Hamilton replies, “I will not go at present, ask no further explanation”.[39]

At this point, the Prince’s strategy takes an even more unpleasant turn. Between 26 and 28 July, Hamilton seems to have written a letter to him that doesn’t survive. His response,[40] dated 28 July, indicates that in that letter (which, he acknowledges, was stained by her tears) she outlines some “misfortunes”, says that she had wishes she had never seen him, and presumably indicates once again that she wants to leave her post. In response, the Prince tells her – in what seems to be an attempt at emotional blackmail – that she’s perfectly safe at present, but that if she leaves, people will have reason to believe that there was a relationship between them. In that same letter, he warns her, “the World… would construct the innocent visits of my Messenger, as well as the little attentions I have shown you… into some private reasons, & they would then think they had found out a cause for your departure which I do not think of a nature fit to be mentioned to a person who has such disinterested, honourable, & virtuous notions as my dearest friend has”.[41] Perhaps feeling that his meaning isn’t clear enough, he reiterates, “if you was to go soon you would not only ruin me in the opinion of the World, but in what is much more dear to me in the eyes of my Parents, for I could not conceal the agonies I should feel” [italics mine].[42]

What had given rise to Hamilton’s sharpened anxiety was, probably, the realisation that in the claustrophobic environment of the Court, people were beginning to notice the Prince’s attachment to her, and to draw their own conclusions.

Gossip and scandal

At some point in early August, William Ramus, a Page of the Backstairs, seems to have become curious about the relationship between the Prince and Hamilton – and, on the evening of the Prince’s birthday (12th August), he apparently probed him about it over a drink. Whatever George said in response seems to have made its way swiftly around the Court and back to Hamilton herself. Hamilton, who had long thought Ramus a “little noxious animal”,[43] reproves the Prince about his indiscretion. She warns him that further “confidence[s]” made to “insignificant character[s]” will result in the withdrawal of her friendship: “I acknowledge I shall have no ambition to be rank’d among the number of your friends if they are all of the same class”.[44] She charges him, however, not to reproach Ramus for his own indiscretion: presumably she didn’t want to fan the flames of the Page’s suspicion any further.

The Prince protests his innocence. He only told Ramus, he insists, that he thought Hamilton “a most agreeable Girl, & then I drank [your] health”.[45] But Hamilton seems unconvinced, and throughout the remainder of August and the beginning of September she apparently received more teasing from either Ramus or another (unnamed) Court gossip, described by the Prince as a “foolish, vulgar meddling woman”.[46] For several days, she seems to have treated the Prince with marked coldness, resulting in him imploring her, “[b]e not too hasty in crediting the reports of prating idle people, who will propagate ill & bad reports merely for the pleasure of talking”.[47]

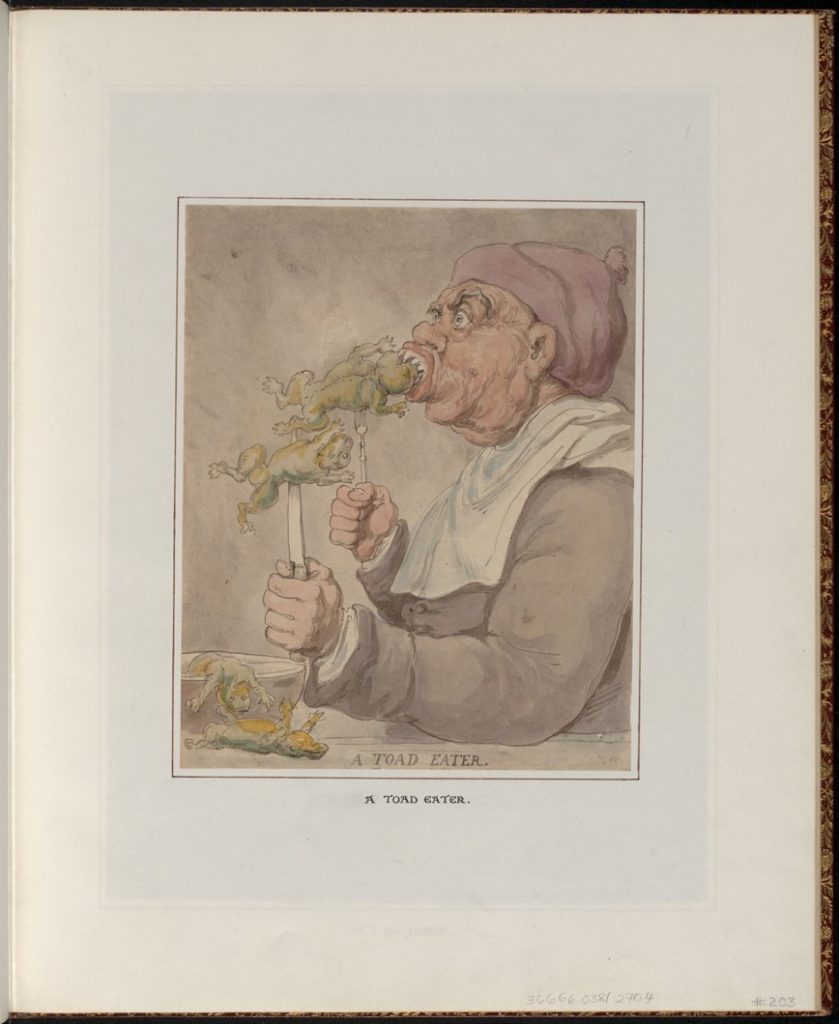

There are times, though, when it’s difficult to believe that the Prince’s aim is really to put Hamilton’s mind at rest. On several occasions, he actually takes it upon himself to report malicious Court gossip about Hamilton to her directly. For example, he tells her that an unnamed gentleman, seeing her walking with the Prince, remarked that he “never saw a plainer girl [than Hamilton] in all his life”.[48] On another, he tells her about a caricature that somebody has drawn of her with a toad in her mouth (i.e. implying that she is a toad-eater, a term used for an over-obsequious dependant).[49] On yet another occasion, it seems that he insinuated that she was unpopular or friendless. This insinuation doesn’t survive, but her response to it does: “So you are vain enough to suppose I shall, from all Your fine Speeches & protestations begin to imagine You are the only person in the world that really cares for poor Miranda [the nickname used for Hamilton by her friends]”.[50]

Thomas Rowlandson, ‘A Toad Eater’, 1788-1821

© Albert H. Wiggin Collection, Arts Department, Boston Public Library

Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online

https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:tq57pk274

It’s unclear whether the Prince’s tittle-tattling is some sort of attempt to curry favour with Hamilton, to destabilise or isolate her, or something else. In any case, it appears to fail. Hamilton laughs off any comment on her looks or her relative poverty.[51] She jokes that she’s surprised she gets off so lightly, and gently encourages him to rise above the silly gossip of the Court.[52] This is in marked contrast to the genuine distress and anxiety she seems to feel when it’s her relationship to the Prince that is under scrutiny.

Why so sensitive?

Perhaps it’s worth taking a moment at this point to ask: why was Hamilton so terrified about her correspondence with the Prince being noticed and talked about? One could be forgiven for thinking that there were worse fates at this time than being the avowed favourite of the future King. Over the next few years, many women – Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson, Elizabeth Armistead, Grace Dalrymple Elliot, and most famously Maria Fitzherbert – would succumb to the Prince’s advances, and some of them didn’t do too badly out of it. Why wasn’t Hamilton more flattered by, and receptive to, the Prince’s declarations?

Leaving aside the issue of personal attraction (or, more likely, a lack of it), the answer lies partly in Hamilton’s socio-economic status. She was descended from a noble family and connected by blood or marriage to the powerful Greville, Napier and Stormont clans – but, compared to most people in the circles in which she moved, she had very little material wealth of her own. She was an orphan, without brothers or sisters. If she left Court (which was clearly her ambition, at some point, to do), she’d depend for her sustenance on the rent from a house that her mother had left her, and a small settlement that her uncle Frederick managed on her behalf. (Once she did leave Court, and before she married, she lived a relatively frugal life in accordance with this modest income. She lived in an unusual house-share arrangement with two friends in order to split household expenses, she borrowed a friend’s carriage for any long trips that she needed to make, and she often lamented her lack of income to buy the things she wanted most – books.)

This might not sound too bad – and of course, by many people’s standards, it wasn’t! But a woman of Hamilton’s class wasn’t trained or conditioned to work for a living – and so, she had no ability to generate her own income. If she wanted to be a part of the thriving social and intellectual culture of London – which, being intelligent and sociable, she did – she’d need to either marry a man who could support her, or else stay single but live very frugally and rely on the generosity of friends who would offer her hospitality, introductions and favours such as the loan of a carriage, books, or their servants’ services. Her ability to make that marriage or preserve those friendships – her social capital, if you like – derived largely from her reputation for virtue and respectability. It’s well-known that severe double standards operated in Georgian high society around the chastity of young men and young women, and that the ton could be ruthless to young women whose virtue was in question. Any whisper of an illicit liaison with the Prince would have cast Hamilton as an immoral gold-digger, incurred the wrath of the King and Queen, shocked and alienated her friends, and tarnished her marriage prospects for good.

In fact, we can turn to Mary Hamilton’s own words to see what’s at stake. On 5th September, she laments

“the unfortunate necessity of acting in a clandestine manner… if by any unforeseen chance it should hereafter be discovered – the two persons most dear to you [the Prince’s parents], would naturally judge me with great severity… Your Mother would detest me as being a most designing artful character – not a human creature… not even my best friends would do me strict justice… How would those who are devoid of sentiment deride the declaration of a disinterested & pure friendship subsisting between persons of such different situations in life”.[53]

Finding fault, finding friendship?

The Ramus affair seems to have blown over for a while (though we’ll return later to the question of whether malicious whispers had reached Queen Charlotte’s ears). Hamilton still had a lot on her plate, though, as the Prince’s passion continued unabated over the autumn. The correspondence shows that he sent Hamilton bouquets of flowers at least twice a week (not exactly in keeping with her pleas for discretion).[54] On 19th August he admits sneaking into her Windsor apartment and, finding a sprig of foliage that she had worn as a bouquet, “seiz[ing] it and kiss[ing] it with a fervour beyond expression” before placing it in his bosom.[55] And, later in the autumn, he starts to become jealous of her friendships with other men – particularly her family friend Lord Napier, whom she’d known since childhood.[56]

Hamilton continues to respond patiently and consistently to the Prince’s overtures: “you should labour under no mistake respecting me, know I never will encourage you to express any other term than friend”.[57] When he succeeds in moderating his language towards her, she calls herself his “real, true & affectionate friend”[58] and his “tender & affectionate Sister”.[59] When his behaviour is erratic or indiscreet, she uses “Sir” and “your Royal Highness“, reminds him to be “tender of my fame & honor”, and hints that she will withdraw her friendship if he doesn’t better prove that he deserves it.[60]

Throughout the autumn, Hamilton increasingly casts herself in a new role: that of the Prince’s severe moral advisor. In August, he’d asked her to “make all the remarks you can upon my conduct, give me all the advice you can”.[61] Hamilton takes him at his word. She provides a “terrible black list”,[62] reprimanding the Prince severely, over several letters, about his bad language,[63] vanity and susceptibility to flattery,[64] tendency to boast and ignore advice,[65] and extravagant, foppish dress sense.[66] She recommends that he read moral essays about the impropriety of swearing,[67] and pours cold water on his enthusiasm for racy novels.[68]

This persona of stern instructress seems to offer Hamilton some respite from the romantic role in which the Prince insists on casting her – to give her, in other words, a part that she felt comfortable playing. Although occasionally William Ramus stirs the pot again,[69] and Hamilton suffers from “a melancholy apprehension” of trouble and disgrace,[70] her correspondence to the Prince from November and early December feels, to me, generally more relaxed than it had been previously. Though frequently scolding or reproaching him for his shortcomings, she appears, at some moments, to genuinely value his friendship and fear the loss of it: “When you cease being interested about me tell me so that I may not run the hazard of having my pride mortified by your contempt”.[71] She also, for the first time, appears to send him an unsolicited gift: “a Ring set with Brilliants”.[72] He thanks her in emotive terms for this present on December 4th: but the very next day he would write her a letter that would change the course of their correspondence, and mark the beginning of its end.

The end of the affair

“I was delighted at the Play last Night”, the Prince writes to Hamilton on 5th December, “& was extremely moved by two scenes in it, especially as I was particularly interested in the appearance of the most beautiful Woman, that ever I beheld”.[73] This was the actress Mary Robinson, an extraordinarily interesting woman in her own right and in later years a very talented poet. The Prince admits later in the letter that he has seen her both on and off the stage, and now considers himself to be in love. He declares his intention to tell Hamilton “every thing relating to this affair”, and finishes the letter imploring her to “pardon… pity… [and] comfort” him.[74] Also, not to tell his parents.

Mary Robinson (née Darby)

by Samuel Haydon, after George Romney

(1780-1781)

NPG D39813

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Hamilton’s response to this declaration, dated two days later, is concerned but not unsympathetic. She doesn’t endorse his choice – “a female in that line has too much trick & art not [to] be a very dangerous object”,[75] she warns him, reflecting a contemporary misogynist prejudice against actresses – but she doesn’t reprove him either, and doesn’t seem to find the news surprising (she had, after all, been telling George for some time that when he started to see other women outside the confines of the Court, he would find Hamilton herself less enchanting).[76] She makes it very clear that she doesn’t think she has anything to “pardon” him for.

However, in subsequent letters her tone quickly becomes markedly more negative, probably because she’s learned what the Prince knew all along – that Robinson was already married, with a child. She implores George not to “lay yourself open to the world in a character to which you would blush to sign your name”.[77] But the Prince shows himself, all of a sudden, newly deaf to her advice. He brushes aside her concerns by asserting that Robinson is unhappy in her marriage (which was true),[78] and jokes about her other lovers such as his friend Sir John Lade. He also starts to excuse himself for not writing to Hamilton more often or at greater length. The religiose language that he has used to address her in the majority of the correspondence is also markedly absent from his letters dated after December 5th.

By mid-December, Hamilton seems to feel that it would be best to put an official end to the correspondence between them, since the Prince has basically stopped writing to her – and when he does, he cannot drop the “detestable Subject”[79] that she feels is “unfit for your Sister”.[80] This is one of her last letters to him:

As I plainly perceive my friend that it is a very great inconvenience to you to continue a correspondence with me & as your politeness will perhaps induce you to give yourself the trouble of keeping it up – permit me to tell you I free you from the constraint – Adieu That you may be happy is the first wish of my Heart – & if the knowledge of the steadiness of my friendship will afford you any satisfaction – Know that I shall ever be the same – nor shall I ever deviate from my professions – for they were made with sincerity.[81]

It is difficult to judge the tone of this letter. I imagine that Hamilton did have very mixed feelings about the Prince’s fling with Mary Robinson and sudden coolness towards her. She was probably sincerely grieved for him, since this didn’t bode well for his moral character and she knew how upset his parents would be. She was also probably a little relieved that he had transferred his affections to a different, less vulnerable object. She may have been chagrined at the swiftness with which he’d dropped their correspondence and forgotten their friendship. Most of all, I wonder whether she felt afraid. Up to this point, the main card she’d had to play in their relationship was the threat of withdrawing her favour or friendship. If the Prince no longer cared for that, what was to stop him saying whatever he liked about her, to William Ramus or anybody else?

As far as we know, the correspondence between the Prince and Mary Hamilton finished with the year 1779. Hamilton herself remained at Court until 1782, after which she finally secured permission (on a second attempt) to resign and pursue the “independence & Liberty” she had always craved.[82]

Reading the Prince’s profusions

It looks as if Hamilton was very wise indeed to keep the Prince at arm’s length. But was he ever sincere in his declarations of love, before Mary Robinson crossed his eyeline? Or was the pretty sub-governess just a bit of fun to him? It’s difficult to say for sure. At one point he refers to himself as Hamilton’s hopeful “future H——–d [Husband]”,[83] and at another he mentions a desire to indulge in “the Joys of Matrimony” with her.[84] But at other times, he admits that his “rank” would prevent their union,[85] thus casting a dubious light over his former extravagant hints.

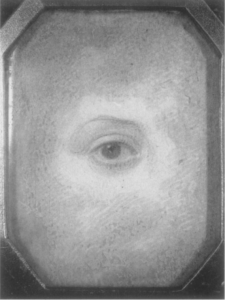

Turning for a moment to George’s later life can give us an interesting perspective on the sincerity (or otherwise) of his declarations to Hamilton in 1779. His conduct towards her – relentless pursuit, ignoring boundaries, and emotional blackmail revolving around threats and performances of suicide – foreshadows his much better-known behaviour later in the 1780s towards women such as Maria Fitzherbert.[86] As Christopher Hibbert notes, the Prince “bombarded” Fitzherbert with letters and repeatedly threatened to kill himself if she didn’t acquiesce to his demands (on one occasion staging an elaborate scene of attempted suicide, which probably involved creative deployment of blood from a medical procedure). Stella Tillyard adds to this the slightly creepy fact that one of the Prince’s letters to Fitzherbert when she had moved to France to get away from him was “accompanied by a little painting of one of the prince’s blue-grey eyes, floating against an azure ground. He was not letting her out of his sight”.

Richard Cosway, ‘The Eye of the Prince of Wales’, ca. 1785.

Private collection, artwork in the public domain.

Image reproduced from Hanneke Grootenboer, ‘Treasuring the Gaze: Eye Miniature Portraits and the Intimacy of Vision’, The Art Bulletin, 88:3 (Sept. 2006), 496-507.

Of course, the Prince did in fact marry Fitzherbert in 1785 (though illegally, since she was a Catholic and his father had presciently passed the Royal Marriage Act in 1772 to militate against rash royal alliances). It is possible, if Mary Hamilton had wanted to play the affair differently, that George might have put his money where his mouth was and actually found a way to make her his (illegitimate?) wife. But, crucially, Hamilton did not want to play it differently – and she was in a very different situation to Fitzherbert, who was a wealthy widow of independent means. The Prince repeatedly ignores her clearly stated wishes, risked her reputation, and undermined her precarious position at Court and in polite society. He may or may not have believed himself in love at certain points – but his actions were nonetheless inconsiderate in the extreme.

Corroborating evidence? A letter to Charlotte Margaret Gunning

So far, I’ve been referring solely to the letters between Hamilton and the Prince. But if we want to get the fullest possible picture of the relationship between them, then we might want to consult other records of their feelings and thoughts as the events of 1779 unfolded. Unfortunately, the pickings available to us are not particularly rich. Over at the Mary Hamilton Project, we don’t currently know of any other primary sources that provide evidence in George’s hand of his feelings towards Mary Hamilton (please alert us if you do!) Hamilton, however, kept detailed personal diaries throughout her life, including the years that she was at Court. Unfortunately, the diaries she kept between 1777 and 1782 have been lost (again, please do alert us if you have any leads!).

We have some surviving extracts, either printed in the Ansons’ biography or copied out by Hamilton herself in one of the ‘manuscript books’ that she compiled in later life. But these tantalizing chunks are remarkably silent on the subject of the Prince of Wales – and there is nothing relevant to him during the year 1779.[87]

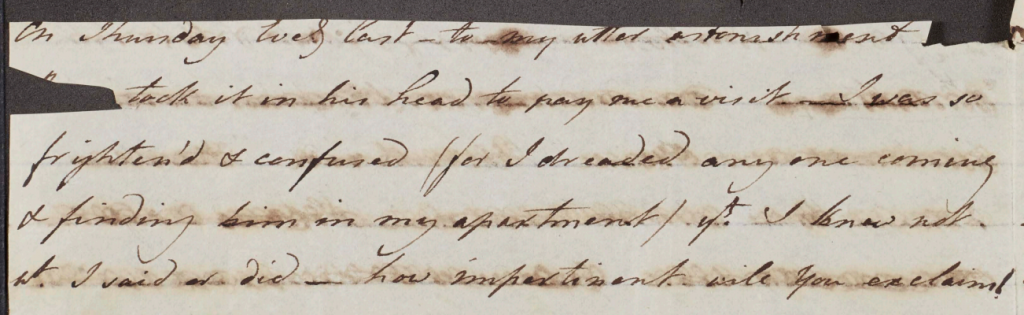

There is one letter dating from the period during which Hamilton and the Prince were corresponding, which might offer some relevant context. On 8 November 1779, Hamilton writes to her close friend Charlotte Margaret Gunning about a gentleman paying her an unexpected visit: the name of the visitor has been cut away from the paper.

On Thursday Evening last – to my utter astonishment – [XXXXXX] took it in his head to pay me a visit. I was so between frighten’d & confused (for I dreaded anyone coming & finding him in my apartment) that I know not what I said or did – how impertinent, will you exclaim! – but what will you say when I tell you he afterwards went to that foolish Woman you have heard me mention – & said he saw my confusion – that he wish’d he had taken advantage of it to make a declaration of his passion – that he could no longer bear the torture of suspense he had suffer’d two years – that it was better to know his doom – that he should shortly be in possession of a 1000 a year &c, &c how happy should he be to have me share his fortunes – then cry’d & rav’d & was in despair. – did you ever hear such stuff? for my part I know not how to act – I dare not behave rude, and I must acknowledge his behaviour to me is perfectly respectful.[88]

Mary Hamilton to Charlotte Margaret Gunning, 8 November 1779 John Rylands Library, HAM/1/15/2/1

Was this unwelcome visitor the Prince of Wales? It’s possible that it might have been. The invasion of Hamilton’s private space, the melodramatics and the indiscretion match up rather well with his conduct recorded elsewhere. The mention of a “foolish woman” matches nicely with the “foolish, vulgar meddling woman” who, along with William Ramus, caused Hamilton such anxiety in August and September.[89]

But it’s far from certain. Mary Hamilton also suffered from the unwanted attentions of other men while at court (principally a Mr Stanhope and a Mr B-) and the excised name means that we can’t be sure it wasn’t one of them instead.[90] Certainly, her “astonishment” at the visitor’s decision to enter her apartments sits oddly with the fact that the Prince had already been pestering her for several months – one would imagine that she’d have come to expect “such stuff” from him by November. But perhaps invading her apartment while she was there was a new impertinence even for him. Or maybe this was simply an aspect of Hamilton’s framing of the incident for Gunning’s benefit, to underline her objection to the invasion. The description of the visitor’s general “behaviour” as “perfectly respectful”, and a marked contrast with his reported “rav[ing]” is also a bit odd – though we should remember that most of George’s improprieties took place on paper, not in person. In the flesh, he might indeed have treated her with perfectly appropriate courtesy.

The only piece of additional information that we have about this visitor’s identity is that he told a “foolish Woman” that “he should shortly be in possession of a 1000 a year”. Initially, I thought that this rather conclusively crossed George off any list of suspects. He wouldn’t receive any official allowance until he was twenty-one, which was four years away, and then it would be much more than a thousand a year.[91]

But then an idea occurred to me. According to several biographers, when George turned eighteen, he entered a constitutionally awkward state in between childhood and independence. He was allowed his own “establishment” and more freedom in his movements, but he had to wait another three years until he was granted his enormous official allowance and established in Carlton House.[92] During this time, he must have had some access to ready cash. Could it be that he expected, or thought it reasonable to expect, that during this liminal period he’d have an informal allowance of a thousand pounds per year? Though it might be coincidence, a thousand pounds seems to have been the sum allocated to his sisters as spending money some years later.[93] And it would make sense, in that case, for the seventeen-year-old to brag about the financial windfall that would come with his approaching birthday.

I haven’t yet established whether there might be anything in this theory. Unfortunately, the records of the Prince’s’ finances preserved in the Georgian Archives only seem to begin a few years later in 1783 – I hope to be able to investigate this more fully when access to the archive is easier.[94] Until such time as I find conclusive evidence that George might have believed (or simply bragged) that he would “shortly be in possession of a 1000 a year”, we must accept that the identity of Hamilton’s visitor remains unknown. However, it does at least offer an insight into how she expressed her feelings to a sympathetic friend about such a pursuit. She was “between frighten’d & confused”, and “dare[d] not behave rude”. This is not a love story.

Corroborating evidence: Hamilton’s diaries, 1782-1785

In the years following her departure from Court, before she married and moved away from London, Mary Hamilton often crossed paths with the Prince. We’re lucky enough to have a full run of her manuscript diaries between 1782 and 1785 which, along with her letters to other friends, can offer some clues about how she remembered her uncomfortable situation at Court.

Once again, I interpret this evidence differently to previous biographers. The Anson sisters offer a diplomatic impression of well-wishing: “Miss Hamilton never ceased her interest in the Prince, and always looked for the best in him, and he always treated her with courtesy when they chanced to meet”.[95] Hibbert, in his biography of the Prince, hints at positive fondness: “The Prince and Mary Hamilton remained on friendly terms, however, and often met in later years… The Prince always spoke of her with affection and respect, and she, when criticisms of his behaviour were voiced in her presence, ‘took his part’ as often as she could”.[96]

In fact, Hamilton’s diaries contain accounts of several incidents that indicate she was embarrassed by the Prince in public, scornful of him in private, and wary of him when they crossed paths – which, at least immediately following her departure from Court, she tried to avoid as much as possible.

It’s only fair to say, before we get to these incidents, that most of Hamilton’s references to the Prince are studiedly neutral. She notes when she sees him in public places – including any gestures that he makes towards her, such as bowing, kissing his hand, or talking to her. She notes, too, the many occasions that a friend tells her the Prince asked after her. But she doesn’t often comment explicitly on what she thought, or how this made her feel.

She also notes occasions when the Prince is mentioned in conversation at the social gatherings she attended. These mentions aren’t often favourable. This was the period when the young Prince, now in the full throttle of his own much-desired “independence”, was exciting much gossip due to his affairs, gambling and general hell-raising. Hamilton tends to simply report what she hears, rather than offer her own view or describe her part in the conversation. But there are exceptions – like the occasion in 1784, when the company is lamenting the Prince’s “disregard of all, even apparent propriety of behaviour” and Hamilton notes, “I took his part when I could”.[97] Smoothly substituting “as often as she could” for “when I could”, Christopher Hibbert sees this occasion as evidence for the “friendly terms” on which Mary Hamilton and the Prince remained during these years. I’m more inclined to see the dry underline of “could” indicating that in fact, Hamilton could not in good conscience take the Prince’s part very often at all.

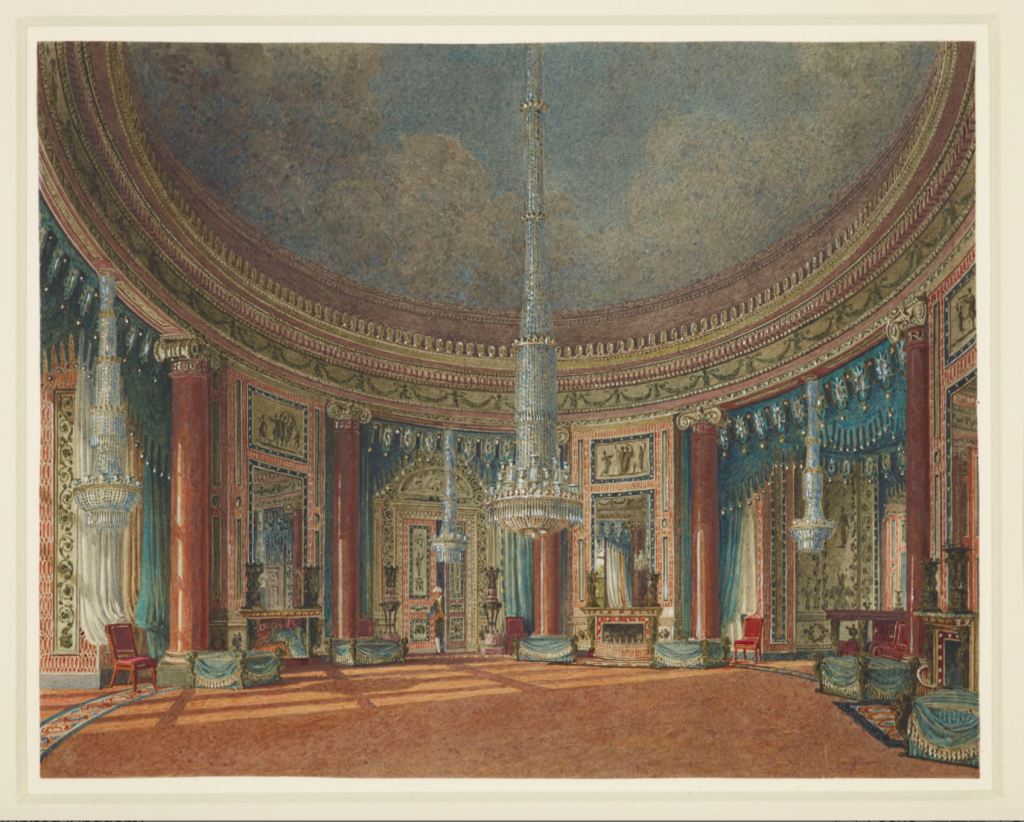

The first incident that indicates Hamilton’s feelings about the Prince were less than positive occurs in spring 1784. The Prince asks Hamilton’s cousin Lady Stormont to invite her, on his behalf, to a ball and supper at Carlton House. Hamilton “said I wish’d I could in a handsome way excuse myself”, but Lord and Lady Stormont, and other relatives, tell her that they are “of opinion I ought not to refuse”.[98] Hamilton appears to be nervous in advance of the ball, gathering endorsements of her attendance from no fewer than eight respected friends. But, in the event, she attended the gathering, and the evening passed without unpleasant incident. Afterwards, she gives her verdict in her diary:

In short it was a fine entertainment & as well conducted as possible for so few great a Number of People – The Prince’s attentions were properly divided & nothing in my opinion could be more proper – more gracious more like a Gentleman & a Prince than his behaviour – what a pity that one who know so well to how do what is right ever fails of doing so! As soon as we came out of the Supper Rooms – I being very prudent got Mr. Digby to conduct me to my Chair & came home about ¼ before 4. I hear Carlton House was not clear’d before 9 in the Morning.[99]

The Circular Room, Carlton House, c. 1817

by Charles Wild (1781-1835)

RCIN 922177

© Royal Collection Trust

https://www.rct.uk/collection/922177/the-circular-room-carlton-house

This extract suggests Hamilton’s relief that the Prince’s attentions were “properly divided”, and indicates that his good behaviour on the night presents something of a contrast with her expectations. Most striking of all is her description of her own conduct as “prudent” in getting Stephen Digby (an old friend from the court days) to conduct her to her chair. She clearly felt that it would be unwise to make this short journey alone.

As 1784 wore on, the Prince’s reputation deteriorated more rapidly. By the autumn, his affairs with Elizabeth Armistead and Maria Fitzherbert were the talk of the town, and Hamilton clearly felt that he was better avoided. On one occasion, she notes “I saw the Prince of Wales who pass’d by to go to Mrs Armsteads – fortunately he did not see me [my italics]”.[100] On another occasion, just after Christmas, she wasn’t so lucky.

The Prince of Wales pass’d the Coach in Company with 3 Gentlemen – he smil’d, kiss’d his hand several times & made me a graceful bow – the Carriage proceeded & he walk’d on – presently he return’d. The Servants were calld to stop & he came to the Coach door – His companions waited at the end of the Street. The following Dialogue took place – (dont look Yellow now.) He asked me to give him my hand in token of friendship, said how happy he was to see me & that I look’d quite well. “I thank you Sir I am very well." “I have been very ill & am now far from well.” “I heard You were ill Sr & am sorry to hear Your R[oyal]. H[ighness] speak so hoarse.” “I never see any of Your relations or friends that I do not enquire after You & send you messages.” “I have, Sir, been inform’d of your kind remembrances.” “Ought I to congratulate You?" “No, Sir.” “When may I do so? When shall You change Your Name?” “Sir, there are affairs to settle, and it will not take place soon.” “You have been sometimes at Bulstrode – near 3 Months – I made particular enquiries when You was there to know if my Father Mother & Sisters had ask’d for You & was much provoked & shocked to find they had not.” “Oh Sir, I did not expect it, nor does it signify.” “Where are You going?” “To dine with the Baron & Baroness.” “Do You still live with them?” “No, Sir.” “In C[larges]. Str[eet].?” "Yes, Sir.” “Farewell, God Bless You.” I bow’d in reply – & away he went. He kept my hand the whole time, which greatly distressed me as there were many bystanders.[101]

Hamilton was writing this account to her fiancé John Dickenson, whom she would marry the following year. Her phrase “dont look Yellow now” seems to be a teasing injunction to restrain his jealousy – she’d clearly told him about the Prince’s pursuit of her at Court. But there is little indication, in her reported dialogue, that she feels any residual fondness for the Prince that might reasonably give rise to such jealousy. She initially tries to pass on without conversation, and once the Prince has called her back, she keeps her answers to his questions short and non-committal. In the last line, Hamilton reveals that throughout this long exchange, the Prince has kept hold of her hand. This was not a usual way to treat an old acquaintance, and her “distress” reflects this fact, “as there were many bystanders”.

John Dickenson is also the recipient of the journal-letter in which Mary recounts her last, and perhaps most important, encounter with the Prince. In March 1785, she tells her fiancé, she was attending “a Grand Concert” when Colonel Gerard Lake, an old acquaintance from the Court days and a renowned favourite of the Prince’s, engaged her in “a curious conversation, the particulars of which I shall not venture to send by the Post” and which she “hope[s] was not overheard”. “I find”, she tells Dickenson, “that he had found out the part I acted when under a disagreeable situation – he said he knows I had been Cruel &c. He ask’d much about You”. It seems highly likely to me that Lake is referring to the Prince’s pursuit of Hamilton here. If so, it seems that, in telling Lake about it, George had been more indiscreet about his feelings for Hamilton than even she had feared.[102]

Hamilton then goes on to say something remarkable to Dickenson. “You know”, she writes, that “he [Colonel Lake] is young Maralls favorite – he told me he RH was coming, so I for reasons chose to get away – he however came in before my Chair was ready – but I stood behind, & he passed through ye Room without seeing me”.

What is interesting to me here isn’t the fact that Hamilton was (once again) trying to give the Prince (or RH, i.e. his Royal Highness) the slip. It’s the name she uses for him: ‘young Marall’. In her journal-letters to Dickenson, Hamilton uses codenames for her acquaintance, presumably from fear that their correspondence would be intercepted. When she edited these letters later in life, she sometimes glosses the codenames (where she is being complimentary or neutral) so that the interested reader can see who’s who: Elizabeth Vesey is ‘Fairy’, Elizabeth Montagu is ‘Attica’, etc. These names are generally drawn from literature, history, or mythology, and they usually bear some sort of reference to an aspect of the bearer’s character.

One code name that Hamilton never glosses is the one that she uses for the Prince of Wales: it is diligently crossed through, beyond recovery, on almost every occasion. This is the one instance I’ve found where she omitted to do so. Whether she let it stand because she thought the bearer’s identity wasn’t clear from context, or whether she simply missed it as she went on her censoring rampage, it’s impossible to say.

But what does ‘young Marall’ mean?

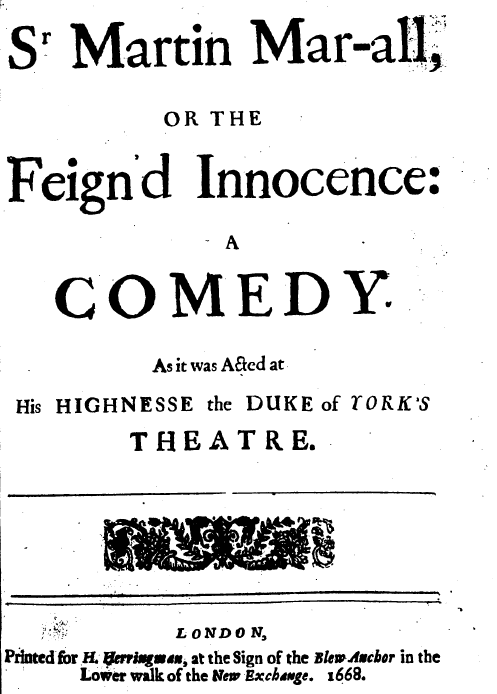

My best guess – inspired by the canny surmises of our PI Hannah Barker and the meticulous research of Co-I David Denison around Hamilton’s codenaming practices – is that this is a reference to John Dryden’s 1667 comedy, Sir Martin Mar-all, or the Feign’d Innocence. Hamilton was fond of Dryden’s poetry and drama, and she reads or quotes him on several occasions throughout her diaries, letters and manuscript books. In the dramatis personae for this play, Sir Martin Mar-all is described bluntly as ‘A Fool’. He is, moreover (the plot suggests) a lecher and a coxcomb, who is mocked by all who know him and is eventually outwitted by a clever servant.

Title page, Sr. Martin Mar-all, or, The feign'd innocence a comedy as it was acted at His Highnesse the Duke of York's theatre.,

John Dryden,

London: Printed for H. Herringman, 1668.

Accessed via Early English Books Online (EEBO)

Such is the code-name that it seems Hamilton and her fiancé chose to refer to her old “friend” and their future king.[103] Or at least, that’s our best guess so far.

Lasting effects

Though Hamilton generally seems to have escaped her “disagreeable situation” with her reputation intact – and recovered to the extent that she could joke about it with her future husband – this doesn’t mean we should assume she wasn’t negatively affected by the experience. On the contrary, I think that the Prince’s harassment may have cast a pall over her (already ambivalent) feelings about her time at Court – and that it possibly also coloured her subsequent relationship with the rest of the Royal Family.

According to the Ansons’ account, Hamilton left Court in November 1781 for reasons relating purely to her health, and she retired with the “esteem and affection of a wise and good Queen”.[104] But it seems to me, on a close reading of the diaries from the early 1780s, that the circumstances of Hamilton’s departure might have been a little more complicated than this. During the early 1780s, she seems to have been acutely sensitive to gossip surrounding her reasons for leaving Court. She never seems to have regretted her decision to leave (on one occasion, upon the King’s birthday, she remarks, “I spent a tranquil day not envying the fine folks at the Birth day but enjoying my liberty”.)[105] But she does seem to have worried that people might think she left for the wrong reasons. On several occasions, her diary records that she offers a frank account of her reasons for quitting Court to an older friend whose advice she respects, who subsequently approves her conduct and vindicates her decision.[106] She wouldn’t have done this, surely, if she wasn’t worried that they might otherwise have somehow got the wrong end of the stick.

Relatedly, it seems that the relationship between Hamilton and Queen Charlotte, who was initially so “kind” to her, was somewhat strained by the time she departed. Hamilton’s mentions of the Queen are generally cryptic, but a few clues can be gleaned directly from her diaries, mostly from the period immediately following Hamilton’s engagement to John Dickenson. It seems that no member of the Royal Family (except, ironically, the Prince of Wales) offered their congratulations or sent her good wishes. Hamilton notes that her uncle William “was severe in his censure of on the Queen for her conduct towards me”.[107] Her cousin Lady Stormont takes a similar view, describing herself as “much provoked” by the Royal Family’s “behaviour”, which she characterizes as “shameful”.[108]

Perhaps the most damning evidence comes from the novelist Frances Burney, who knew Hamilton personally and whose life shadows hers in some rather interesting ways.[109] For one thing, four years after Hamilton escaped from Court, Burney entered it as Keeper of the Robes to Queen Charlotte. Like Hamilton, she had no interest in a career as a courtier, and largely took the post to please her family. Like Hamilton, she quickly found her duties exhausting, dull, and stifling to creativity. Like Hamilton, she made her escape after five years or so, pleading ill health. But before she did so, she reported the following “very long & confidential discourse” with the Queen: “the subject, Mrs. Dickenson, formerly Miss Hamilton, & an attendant upon the Elder Princesses”.

I gave her a narration of the beginning & the progress of our acquaintance, & she opened with the utmost frankness in giving her opinions & thoughts. When they are upon Characters, living, I will never commit them to paper, except where so closely blended with my own affairs as to be of deeper interest to myself than to her; or except, also, where they are mentioned with praise unmixt; which is rarely the case where a judge so discerning speaks with entire openness.[110]

Illustration 10.

Fanny Burney

by Edward Francisco Burney

NPG 2634

© National Portrait Gallery, London

I do wish that Burney, on this one occasion, had suspended her discretion. I’d like very much to know what the Queen had to say, so frankly and in such “mixed” terms, about Hamilton.

It’s possible, of course, that the Queen simply resented being abandoned by the young lady whom she thought she’d honoured with her favour and confidences. We know that she didn’t want Hamilton to leave court, and refused to accept her first resignation, just as she later refused to accept Burney’s.[111] But this doesn’t entirely explain her coldness. Indeed, the contrast between the Queen’s treatments of Hamilton and Burney after they left court is illustrative. After resigning in 1791 for very similar reasons to Hamilton, Burney received a pension for life from the Queen of half her salary, and she was frequently invited back to Court to visit the Royal Family.[112] To the best of my knowledge, Hamilton was just frozen out.

Conclusions

In this long blog post, I’ve argued that while the Prince of Wales’s conduct towards Mary Hamilton may or may not have looked like love from his perspective, it looked much more like harassment from hers. I’ve drawn on Hamilton’s own words, largely those preserved in her letters and diaries in the Royal Archives and the John Rylands Library, to show why I believe this. By her own account, she was frightened, distressed, tortured, melancholy, and uneasy. She apparently told the prince in a letter, as her tears stained the page, that she wished she’d never seen him. She told him that she wanted to leave what she later described as a “disagreeable situation”.[113] And she eventually – thanks to her own shrewdness, restraint, and masterful management of the Prince – got away relatively unscathed. After her departure, I think the most charitable word we can use to describe her attitude to the Prince is mixed. She seldom described him in positive terms, frequently mentioned him in negative ones, and made every effort to avoid him.

This is, of course, correspondence with a context. Archives don’t exist in a vacuum: somebody has always, mindfully or otherwise, kept certain things and discounted (or excluded) others. These letters were kept, preserved and curated by Mary Hamilton, and bequeathed to her descendants, before winding up in the Royal Archives. They are not a complete run – there are many gaps and mysteries, and the collection includes far more letters written by the Prince than by Hamilton herself. We know that many of her letters were burned by the Prince at Hamilton’s command. Others were returned to her, after which she would have had the option to destroy or censor any that she didn’t like. Those who held the letters after her death might have censored further (though there’s no particular reason to believe that they did so). We must recognize that we are looking at the record that Hamilton, and others through whose hands her archive passed, wanted to retain.

But we need to be quite careful here. As I researched Hamilton’s relationship with the Prince, I – a young(ish) female researcher in 2021, steeped in the lessons of the #MeToo movement – still caught myself more than once looking at her conduct with almost as critical an eye as her contemporaries, and questioning the veracity of her statements to an unwarranted degree. Did a friendly word towards George, I wondered, mean that she was leading him on? When she threw in a word of praise among several dozen words of criticism, should this be read as evidence that she enjoyed his attentions? Might her lost letters have contained encouragement, or even reciprocation? And did her horror at his liaison with Robinson, which heralded the end of her friendship with him, smack of jealousy?

There is little reason to believe any of these things. There is little reason to believe, in fact, anything other than what the evidence on the page suggests – that the Prince of Wales harassed Hamilton even in the face of her discomfort and distress, and that she did not enjoy it. But these questions kept forcing themselves into my mind, because we are conditioned to view women’s stories with a more sceptical eye than those of men. We are trained to often assume the worst of them, where we presume that boys (who will be boys) are well-intentioned underneath it all. At best, we gloss over women’s accounts of what happened. At worst, we actively disbelieve them.

It is a privilege to work on a project committed to recovering Mary Hamilton’s own voice and reconstructing her experiences as she preserved them for posterity.[114] We are turning up new stories all the time in this archive – stories of intense friendship, companionate love, parenthood and loss, intellectual development, family politics, and national and international affairs. This story of a “disagreeable situation” at Court is not a love story, so we shouldn’t call it one. There are plenty of better reasons to pay attention to, and to celebrate, Mary Hamilton.

Mary Hamilton by Saunders,

From a miniature in a ring given by her to Mr. John Dickenson after their engagement

Frontispiece to Mary Hamilton, afterwards Mrs. John Dickenson, at Court and at Home, from Letters and Diaries 1756 to 1816, edited by her great-granddaughters Elizabeth and Florence Anson (John Murray, 1925).

Footnotes

[1] The full series of letters is held at the Royal Archives in Windsor, where they were digitized and made available online since 2018 on the website of the Georgian Papers Programme. But this is the first time that the letters have been transcribed, all chronologically arranged, and edited so that they are fully accessible and legible for a general modern readership as part of The Mary Hamilton Papers (1743-1826). We make them available with the kind permission of the Royal Archives and the Georgian Papers Programme, for which we are very grateful.

[2] See Christopher Hibbert, George IV, Prince of Wales, 1762-1811 (Longman, 1972), p.14; Stella Tillyard, George IV: King in Waiting (Penguin, 2019), p.24; Michael De-La-Noy, George IV (Sutton Publishing, 1998), p.9.

[3] Mary Hamilton, afterwards Mrs. John Dickenson, at Court and at Home, from Letters and Diaries 1756 to 1816, edited by her great-granddaughters Elizabeth and Florence Anson (John Murray, 1925), hereafter 'Anson & Anson'.

[4] See the Mary Hamilton Papers at the John Rylands Library, Manchester, which contains correspondence, manuscript diaries and other manuscript volumes. I have normalised the text of the original documents to make it easier to understand for readers unfamiliar with the conventions of eighteenth-century writing. Underlines are reproduced from the original documents, but italics are always mine and are marked as such. Please click through to see images of the correspondence itself, and more accurate transliterations.

[5] Anson & Anson, p.50. Taken from a letter now lost.

[6] Anson & Anson, p.54 and pp.98-9. Taken from a journal now lost.

[7] Some of this correspondence has been preserved in the series ‘Correspondence from the Royal Family’ (HAM/1/1).

[8] Anson & Anson, p.55. Taken from a journal now lost.

[9] Anson & Anson, p. 52. Taken from a journal now lost.

[10] See Hester Davenport, Faithful Handmaid: Fanny Burney at the Court of King George III (Sutton Publishing, 2000), especially p.42 and pp.47-8.

[11] Flora Fraser indicates, in her biography of the Princesses, that their brother first started writing to Hamilton after seeing her act as standing chaperone for the Princesses as they worked, read and played cards each evening. They had certainly had the opportunity to exchange at least some conversation, however, as the Prince’s early letters refer to earlier verbal exchanges between them. Flora Fraser, Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III (Bloomsbury, 2012), p.54.

[30] See RA GEO/ADD/3/83/36 in particular.

[33] Sally Holloway, The Game of Love in Georgian England: Courtship, Emotions, and Material Culture (Oxford University Press, 2019), p.14.

[56] RA GEO/ADD/3/83/19 and RA GEO/ADD/3/82/63.

[60] RA GEO/ADD/3/82/28 and RA GEO/ADD/3/83/15.

[63] RA GEO/ADD/3/83/7 and RA GEO/ADD/3/83/13.

[66] RA GEO/ADD/3/83/53 and RA GEO/ADD/3/83/54. Hamilton is particularly severe about George’s tight shoes and oversized shoe buckles. Matthew McCormack has a wonderful piece forthcoming about shoe buckles and fashionable masculinity, which helped me to understand Hamilton’s objections in their broader context – I am grateful to him for sharing a draft with me.

[82] We don’t have much evidence of Hamilton’s interactions with the Prince during the remainder of her time at Court (see my discussion of her lost diaries below).

[86] See Tillyard pp.28-32, Hibbert pp.48-56.

[87] The Ansons include one extract of interest relating to the Prince, dated August 1782 – over two years after the cessation of the correspondence, and a few months before Hamilton finally left Court. “The behaviour of the Prince of Wales towards his Parents upon the loss of his [two-year-old] Brother, P[rince]. Alfred, confirms my opinion that he has a good heart & possesses genuine sensibility of mind – Many wear a mask to conceal deformities – alas, why will he so often put one on to conceal virtues”. (See Anson & Anson, pp.121-2. Taken from a diary now lost.)

[90] A similar instance of censorship occurs in one of Hamilton’s diaries from the later 1780s, when she tells her uncle William of somebody’s “persecution” of her. This conversation is linked with their discussion of Hamilton’s conduct while at court, so it’s possible that she is referring to the Prince: but we can’t be sure. See HAM/2/5, p.51. (Diary citations are taken from the Mary Hamilton Papers.)

[91] According to Hibbert (p.32), the agreed sum on the Prince achieving his majority (after a lengthy process of negotiation between the King and the government) was £50,000, plus the Duchy of Cornwall revenues and a one-off capital payment of £60,000.

[92] Tillyard, p.14.

[93] Thanks to Mascha Hansen, for directing me towards a mention of the princesses’ allowance, mentioned in Flora Fraser’s Princesses, p.71.

[94] This post was written and published during one of the national lockdowns necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks to Karin Wulf for putting me in touch with Mark Mulligan, who pointed me towards the series in the Georgian Papers that might contain material relating to this question: ‘Accounts of the Younger Princes, 1781-1809’ (RA GEO/MAIN/43292-43310).

[95] Anson & Anson, p.90.

[96] Hibbert, p.17, n.

[103] Hamilton and Dickenson seem to have enjoyed a charmingly frank and companionate relationship, which is outlined by Anne Gardner in a forthcoming article. (‘Towards a companionate marriage in late modern England? Two critical episodes in Mary Hamilton’s courtship letters to John Dickenson’, forthcoming. Many thanks to Anne for sharing this work with us in draft.) This is not the only occasion on which they mocked the Prince together during the 1780s. We are currently undertaking work to decipher a fascinating letter from 1789 in which Dickenson appears to light-heartedly compare the Prince to the Devil. The Dickensons appear to have written to the Prince in 1801 to commiserate on an accident that he had suffered – the letter itself is lost, but it is referred to in RA GEO/ADD/3/84/1. However, this might well have been prompted by a mutual acquaintance (who thanks them for their letter on the Prince’s behalf) rather than being an act of goodwill out of the blue.

[104] The Ansons cover Hamilton’s departure from Court on pp. 123-128. The quotation is taken from an excerpted letter from Hamilton’s friend, the writer Hannah More. It is dated November 18th 1782, and indicates More’s understanding, no doubt informed by Hamilton’s report, that her resignation alone did not automatically mean there was a black mark against her name (Anson & Anson, p. 126).

[106] See, for example, HAM/2/5, p.40 and p.51. See also Hamilton’s letter to her friend M. D’Agincourt, reproduced in Anson & Anson, pp.126-128.

[109] See Anne Gardner’s article analysing the relationship between Burney and Hamilton based on an analysis of the letters between them. Anne-Christine Gardner, ‘Downward Social Mobility in Eighteenth-Century English: A Micro-Level Analysis of the Correspondence of Queen Charlotte, Mary Hamilton and Frances Burney’, Neuphilologische Mitteilungen CXIX (I): pp.71-100.

[110] Frances Burney, 11th November 1786, in the Journal-Letter for 1-30 November 1786, in The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney, Volume I, 1786, ed. Peter Sabor (Clarendon Press, 2011), pp.251-252.

[111] According to the Ansons, Hamilton attempted to resign on 25th June 1781. The Queen dismissed her letter of resignation as “the effect of low Spirits” (See Anson & Anson, pp.100-101; original italics). She resigned again on 27th November 1782, and this time the resignation was accepted (See Anson & Anson, p.123 and p.129).

[112] See Davenport, Faithful Handmaid, pp.146-147.

[114] I take full responsibility for the contents of this article, especially any errors. But for any positive aspects, I’m indebted to all the other members of the Unlocking the Mary Hamilton Papers project team – Hannah Barker, David Denison, Nuria Yáñez-Bouza, Cassie Ulph, Tino Oudesluijs and Christine Wallis – who have provided indispensable advice, support, patience and proofing. I must offer particular thanks to Nuria for her heroic check of the finished draft. I’d also like to thank all the members of our Advisory Board, especially Jane Hodson for suggesting that the Prince’s later life might be illustrative, and Nataliia Voloshkova for constructively challenging my interpretation of the correspondence. Many thanks, also, to John Hodgson, Peter Sabor and Lorna Clark.