In this special guest blog post, Aileen Loftus, a second-year undergraduate student at the University of Manchester, writes about her group's experience of 'Editing a Georgian Archive' as part of the Undergraduate Scholars programme.

As part of the University of Manchester's Undergraduate Scholars Programme a team of extremely amateur transcribers were able to have a crack at transcribing a selection of letters from the Mary Hamilton Papers. As a group of five we tackled five letters, one scrappy note and one envelope, before going on to complete a collective research piece based on the content of the letters we transcribed. Learning how mark up our transliterations according to a subset of the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) and XML (eXtensible Markup Language) guidelines was completely new for all of us and we began by attempting the transcriptions solo, before coming back together to help each other figure out any parts we struggled on. This was a mixture of questions about tagging and difficulty deciphering handwriting. A second pair of eyes was really helpful, especially since we were looking at pieces by the same couple of authors, and so had become accustomed to the script. Sometimes someone else was immediately able to read a word one of us had been struggling with for ages – both frustrating and useful.

The Undergraduate team also shared with each other everything that made us laugh. This mostly meant someone had been rude, still in a within-Georgian-letter-ettiquette kind of way.

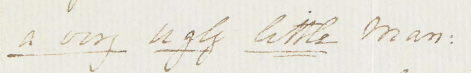

Detail from HAM/1/7/7/2

Several of the letters we transcribed were very chatty letters from Wilhelmina King to Mary Hamilton, whose repeated use of ‘tho’ could have been plucked straight from our whatsapp group chat. In one of the letters (HAM/1/7/7/2) she repeats a description of a Great Duke as a ‘very ugly little man: the length of his nose to his upper lip, longer than the nose itself; very tottering, & weak in make, as well as constitution’, which is a wonderfully descriptive kind of insult, and has made me consider the length of upper lips for the first time. In HAM/1/7/7/3 King also amusingly refers to the death of someone’s elderly mother as convenient, as a wedding is now expected to take place: ‘her Mother who is lately Dead near 100 was always against the match and her daught[er] tho' near or quite 70 was too dutifull to dispose of herself, but that obstacle being removed 'tis expected to take place very soon’. I wonder how she would have felt about being called an ‘obstacle’.

Credit: The Pantiles or Parade, Tunbridge Wells. Photograph. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

I even involved a couple of my housemates in the process in the kitchen as we all struggled to decipher a phrase that turned out to read ‘I have attended the tea drinkings and Pantiles’, where a ‘gs’ had been overwritten with a ‘k’ in ‘drinkings’. This small phrase therefore reads ‘tea drin<subst><del rend="overwritten">gs</del><add>ki</add></subst>ngs’ in transliteration. We also assumed it read ‘tea drinkings and parties’, as an initial googling of ‘pantile’ only brought up a type of s-shaped roof tile, normally made from clay. This didn't seem to fit. The Pantiles is actually a Georgian colonnade in the town of Royal Tunbridge Wells, which made a lot more sense (though less sense than a party). The quirks in the language are one of the most fun aspects of reading the letters, and it was these quirks that we were quick to share with each other. All of my housemates and I now regularly ask if anyone would like to attend a tea drinking, opposed to asking if they fancy a cuppa. We have Wilhemina King to thank.

![[...] here, so only my Lady & U have attended the tea drinkings and Pantiles. the Balls are but just begun & we have [...]](https://www.maryhamiltonpapers.alc.manchester.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/HAM-1-7-7-3a-1024x155.png)

Detail from HAM/1/7/7/3

We all enjoyed the opportunity to work alongside the Mary Hamilton team, and enjoyed the process of reading and transcribing the letters, so much so though that we have chosen to contribute a few more over our summers. It has been a pleasure to be able to contribute to the project.

Our (well checked) letters can now be found in the archive: Aileen Loftus edited HAM/1/7/7/3 and HAM/1/6/8/25; Qiaoshen Hua edited HAM/1/7/7/2 and HAM/1/6/8/4; Tillie Quattrone edited HAM/1/7/7/4 and HAM/1/7/7/5; Lauren O'Connor and Anne de Reynier divided and edited HAM/1/6/8/1.

Aileen Loftus

July 2020